Newsmatro

As the contract deadline of September 14th approaches, a more assertive United Auto Workers (UAW) union finds itself on a collision course with the Big 3 automakers—General Motors, Stellantis, and Ford. The demands put forth by the union, characterized even by its president as “audacious,” include a 46% pay raise, a shortened 32-hour workweek with 40 hours of pay, and the restoration of traditional pensions. These demands have brought the UAW closer to a potential strike.

In response, the automakers, which are currently enjoying robust profits, have swiftly dismissed the UAW’s wish list. They argue that these demands are unrealistic, especially in a fiercely competitive landscape where Tesla and lower-wage foreign automakers challenge the traditional automotive giants. This stark divide in negotiations could culminate in a strike against one or more automakers, potentially driving already-inflated vehicle prices even higher.

This potential strike involving 146,000 UAW members takes place amidst a backdrop of increasingly emboldened unions across the United States. Strikes and strike threats are on the rise, involving diverse groups such as Hollywood actors and writers, significant agreements with railroads, and major concessions from corporate behemoths like UPS.

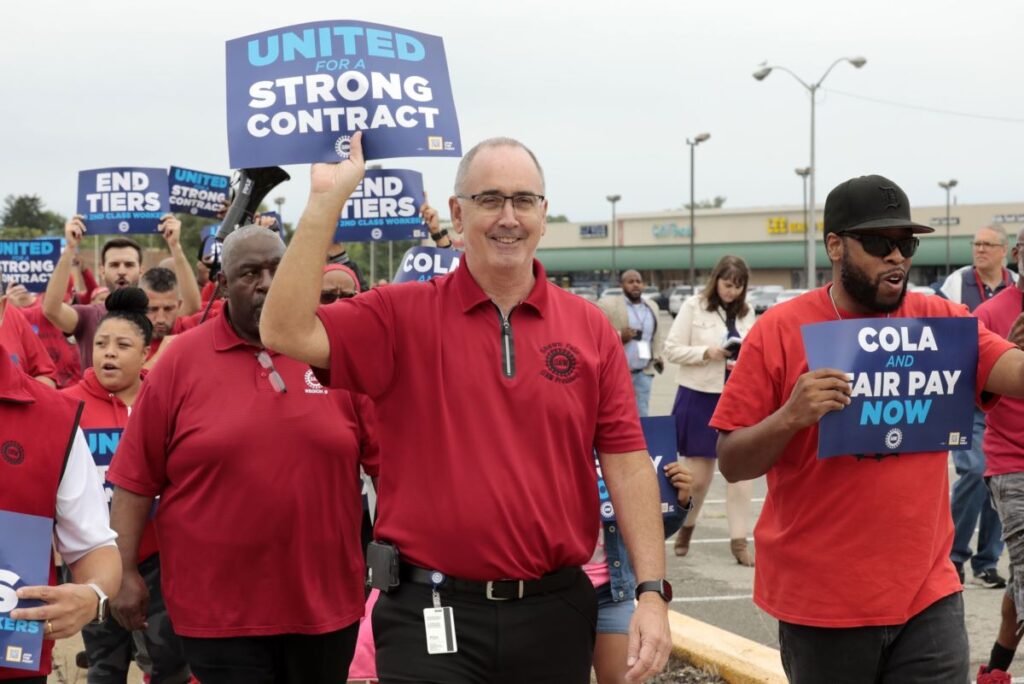

Shawn Fain, the tenacious new leader of the UAW, frames the contract negotiations as a battle between billionaires and ordinary middle-class workers. Fain’s rhetoric reached a crescendo during a recent Facebook Live event, where he dramatically condemned a contract proposal from Stellantis as “trash” and tossed a copy of it into a wastebasket, asserting that it belongs there.

Over the past decade, the Detroit Three automakers have become formidable profit generators, collectively amassing $164 billion in net income, with $20 billion in profits this year alone. The CEOs of these automakers enjoy multimillion-dollar annual compensation packages.

During a speech to Ford workers in Kentucky, Fain highlighted the glaring disparities between the corporate elite and the average worker, citing exorbitant salaries, unnecessary pensions, top-rate healthcare, and flexible schedules for the former while the majority of UAW members lack these benefits.

UAW members have overwhelmingly authorized their leaders to call a strike, and their Canadian counterparts are following suit, with their contracts set to expire four days later. The UAW has not yet announced whether it will select a specific automaker to strike or potentially target all three, which could deplete the union’s strike fund in less than three months.

On the flip side, even a short 10-day strike could cost the three automakers nearly a billion dollars, as calculated by the Anderson Economic Group. A 40-day UAW strike in 2019 alone led to GM’s loss of $3.6 billion.

Recently, the UAW filed unfair labor practice charges against Stellantis and GM, claiming that both companies have failed to provide counterproposals. Fain expressed his disappointment in Ford’s response, labeling it as an insult to the union’s value.

The automakers maintain that the union’s allegations are unfounded and emphasize their pursuit of a fair deal that allows them to invest in their future.

Marick Masters, a business professor at Wayne State University in Detroit, believes that the strong U.S. job market and the automakers’ substantial profits have given Fain considerable leverage. Furthermore, the imminent release of numerous electric vehicles by these companies could face delays due to a strike, and their limited vehicle supply may not withstand an extended walkout.

The key question now revolves around whether the negotiating parties are willing to compromise. Thus far, this willingness has not been apparent.

Fain, who assumed the UAW presidency this spring in the union’s first-ever direct election by members, has set high expectations and encouraged workers to take a firm stance during negotiations.

However, even Fain acknowledges that the union’s demands are audacious. These demands include restoring traditional defined-benefit pensions for new hires, eliminating wage tiers, increasing pensions for retirees, and introducing a 32-hour workweek for 40 hours of pay.

Currently, UAW workers hired after 2007 do not receive defined-benefit pensions, and their healthcare benefits are less generous. The union has made sacrifices in the past, forgoing general pay raises and cost-of-living wage increases to help the automakers manage costs. Although top-scale assembly workers earn $32.32 an hour, temporary workers start at just under $17. Nevertheless, full-time workers have received substantial profit-sharing checks this year, ranging from $9,716 at Ford to $14,760 at Stellantis.

Chris Lindsey, a UAW member building Ford trucks in Louisville, contends that workers deserve a more equitable share of the automakers’ substantial profits, stating, “We keep giving up, but nothing in return. We just want something fair.”

One of the significant hurdles in reaching a contract agreement is the union’s representation at ten EV battery plants proposed by the automakers. These plants, most of which are joint ventures with South Korean battery manufacturers, aim to pay lower wages.

The UAW is concerned that the simplicity of EV production, with fewer moving parts, may result in reduced employment opportunities. Additionally, workers at combustion engine and transmission plants could face job losses during the transition, necessitating alternative employment options.

Fain, a 54-year-old electrician who started in a Chrysler factory in Kokomo, Indiana, is among several labor leaders across various industries who are intensifying their demands and flexing their collective muscle. In 2023 alone, 247 strikes involving 341,000 workers have taken place, marking the highest figures since Cornell University began tracking strikes in 2021 (though still below levels seen in the 1970s and 1980s).

Experts suggest that the automakers would struggle to quickly replace striking workers due to a tight job market, diminished interest in manufacturing roles, and relatively modest wages.

Some auto workers view the recent UPS contract, offering a top wage of $49 an hour for experienced drivers, as a reference point for their negotiations. Others simply hope to approach that figure.

However, automakers argue that an overly generous settlement could saddle them with costs substantially higher than their competitors, precisely as they ramp up EV production. Their inability to unionize Hyundai-Kia, Nissan, Volkswagen, Honda, and Toyota factories has weakened the UAW’s bargaining power, according to Harry Katz, a labor professor at Cornell.

Taking benefits into account, workers at the Detroit 3 automakers receive approximately $60 an hour, compared to $40 to $45 an hour for their counterparts at foreign-based automakers with U.S. factories, largely due to differences in pensions and healthcare.

Should the Detroit companies incur higher labor costs, those costs would likely be transferred to consumers, resulting in more expensive vehicles and potentially impacting their competitiveness with nonunion plant-produced vehicles.

A strike lasting more than a few weeks would exacerbate the existing shortage of vehicles on Detroit automakers’ dealer lots. With robust demand, vehicle prices would rise accordingly.

Masters and Katz suggest that there is still room for negotiation without resorting to a strike. Possible scenarios include a settlement with pay raises, cost-of-living adjustments, enhanced company contributions to 401.